A green and shimmering perch with the distinctive dark stripes over the body has just been placed on the balance. The fins on the stomach and the tail shine red.

“It weighs 250 grams”, says Henrik Dahlgren, marine biologist at the Swedish Museum of Natural History, and moves the fish to a measuring board with a square pattern showing centimetres and millimetres.

“And it’s 27.8 cm long”, he adds.

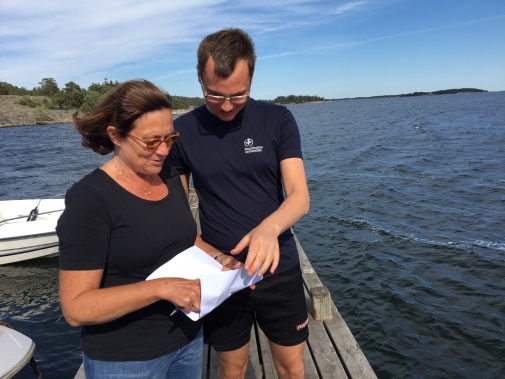

Johan Gustafsson repeats the numbers and writes them down in the protocol.

Johan Gustafsson is a PhD student in Environmental Chemistry at the Department of Environmental Sciences and Analytical Chemistry (ACES) and conducts sampling of perch at Nämdö in Stockholm archipelago during the summer. The sampling is part of his doctoral project where he studies effects of a certain type of brominated substances called hydroxylated polybrominated diphenyl ethers.

“Brominated substances are for example used as flame retardants for furniture, but are also naturally produced by plants in the Baltic Sea, for example, by filamentous algae that are commonly seen on cliffs in the archipelago but also by cyanobacteria. The naturally produced brominated substances occur at high concentrations in several species in the Baltic Sea, including perch. From laboratory experiments, we have seen that these substances can be toxic for fish by interfering with the energy production in the cells, now I want to find out if they can contribute to the reduced health status and population sizes of several species in the Baltic Sea”, says Johan Gustafsson.

High concentrations of these naturally produced brominated substances has previously been detected in perch and it is therefore interesting to continue investigating them.

“There is data indicating that the amount of these brominated substances has increased in fish from the Baltic Sea and it is known that the eutrophication has increased the amount of these substances since the amount of algae has increased considerably. The crustaceans in the water eat the algae and the perch eat the crustaceans or any other fish that, in turn, has eaten the crustaceans, thus moving the substances up in the food chain.”

In order to investigate how the brominated substances affect the fish, Johan Gustafsson will also investigate different health markers, focusing on the effect on the metabolism of the fish, which means the conversion of food to energy.

“It is important to investigate because it is this process that the brominated substances interferes with”, he says.

Sampling on Nämdö once a week

Together with his supervisor Lillemor Asplund, Associate Professor at ACES, he goes to Nämdö once a week from May to September to do the sampling. The sampling takes place during the summer because the algae are abundant during this time of the year.

“We try to examine 15 perches each time, and it should preferably be females. To minimize variations that occur due to reasons other than a shifting environment, the perches should be as similar as possible in all other aspects, then it is easier to follow a trend. But it’s not always easy to catch the fish so sometimes we have to be satisfied with fewer than 15, says Johan Gustafsson.

The possibility of catching fish has increased thanks to the local support for the project on the island.

“It is fun that the project has received good local support, we have been given permission to fish in both privately owned waters as well as waters owned by Skärgårdsstiftelsen, says Henrik Dahlgren.

This day, in the end of June, it is the seventh time that the team goes to Nämdö. In the corf by the wooden pier, 11 fishes are waiting.

“It’s good to be three people, it’s a lot of different things to handle, a little tricky and takes time, so we help each other”, says Johan Gustafsson.

Henrik Dahlgren, who lives on the island during summer, has caught the fish a few days before the sampling takes place.

“This time it was a little harder to catch the fish so I had to move the nets twice”, says Henrik Dahlgren, who works with environmental monitoring in the national monitoring program and is used to taking samples from fish.

All of them can carry out the various moments involved in the sampling, but Henrik Dahlgren is usually the one who dissects while Lillemor Asplund takes care of the blood samples and Johan Gustafsson is responsible for the bile and glucose samples and records the data in the protocol.

15 sampling occasions will be carried out

“What we want to see is the variation during the season. During the summer, the levels of the brominated substances peak and we want to be sure that we collect samples when the fish is as most exposed, which is why we do this so many times. We will then compare the results gathered during the summer, at the peak of the exposure, with the results from spring and fall when the exposure is much lower. In total, 15 sampling occasions will be carried out from May to September”, says Johan Gustafsson.

The table on the porch of the house serves as a temporary laboratory, and it is full of test tubes in various stands, pipettes, bottles, syringes and brown glass bottles with water and ethanol. Next to Lillemor Asplund there is a centrifuge for test tubes and below Johan Gustafsson there is a container that contains liquid nitrogen and a box with dry ice – some of the samples must be frozen immediately, otherwise they will be destroyed. It smells a bit salty and wet from the fish and sea water.

“Oh, no, the blood has coagulated in the tube”, says Lillemor Asplund, holding up the test tube.

There is some hassle with several of the blood samples today.

“I can keep them a little longer in the centrifuge, some of them don´t want to settle, they become milky”, she says.

There are many different samples to be collected from each fish, in addition to blood samples, weight and length, an age determination is made and four different muscle samples are taken togheter with bile and liver, the amount of glucose is also measured in the blood.

One fish is examined at a time, and when all samples are made, Henrik Dahlgren goes down to the dock and collects the next fish in the corf while Lillemor Asplund prepares the syringe used for the blood sample.

“We have to work carefully and bring all samples back to the laboratory at the university”, says Johan Gustafsson.

The samples are very valuable

After September, all samples will be analysed.

“There are many analysis to be done, so a lot of work lies ahead. Therefore, it is important that everything is done correctly during the sampling so that we are able to answer our questions, the samples are very valuable”, says Johan Gustafsson.

The working days at Nämdö are long and involve early mornings and late evenings, but at the same time, the hours of sampling go fast, everyone works efficiently.

“Now I will pick up the eleventh perch in the corf ”, says Henrik Dahlgren, putting scalpel, tweezers and scissors in the ethanol solution to make them clean before the final sample.

When all the fishes have been sampled, Henrik Dahlgren takes on a wetsuit and collects algae and mussels from the sea in small plastic bags. Using an instrument, Johan Gustafsson and Lillemor Asplund examine the sea water to measure the amount of salt in the water, as well as pH, soluble oxygen and temperature.

“We want to know how the environment looks like where the fish lives and keep track of various factors that can affect them and take it into account when assessing the results”, says Johan Gustafsson.

The table on the porch has been cleaned and the instruments put away, the samples are packed for the trip home. Now, they just need to wait for the boat back to Stavsnäs.

About the project

The project to investigate the deteriorating health status of wildlife in the Baltic Sea will last for three years. The purpose of the project is to investigate whether brominated substances produced naturally in the Baltic Sea, including algae and cyanobacteria, could cause reduced health in Baltic Sea wildlife. The project is financed by Formas and in the project, Lillemor Asplund and Johan Gustafsson collaborate with Vrije Universiteit in Amsterdam, where parts of the research are conducted, including some chemical analysis and comparative studies using zebrafish embryos as a model. The project is also a collaboration with fish physiologists at the University of Gothenburg. Johan Gustafsson has also received grants from the foundation Gålöstiftelsen, the Swedish foundation Stiftelsen Hållbara Hav and from the foundation Bengt Lundqvists minne. The grants are mainly intended to fund the sampling and guest research at Vrije Universiteit.