A new warming phase in the Subpolar North Atlantic

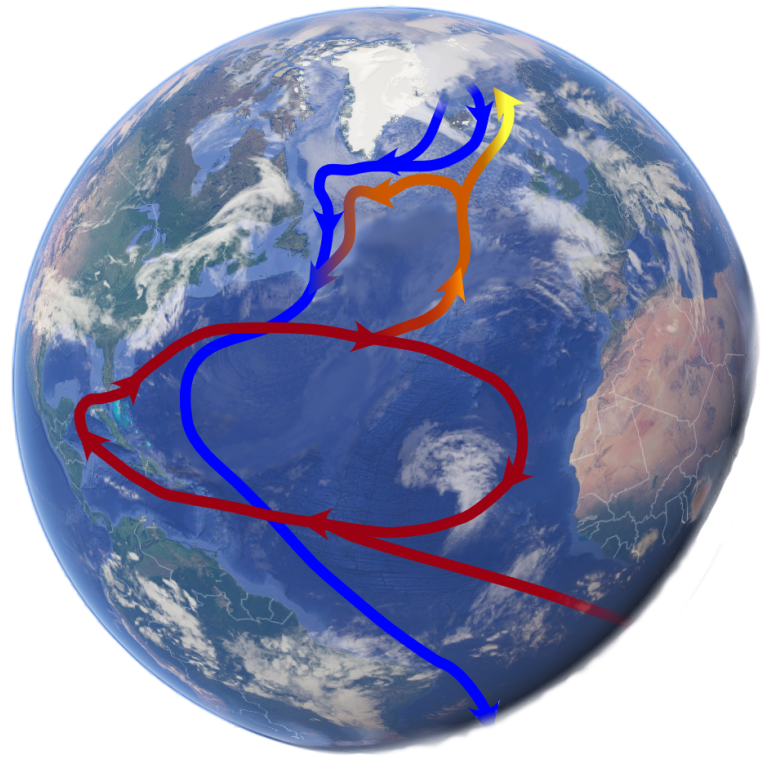

The waters in the Subpolar North Atlantic – the area between Greenland, Iceland and Scotland – are an important part of the Atlantic overturning circulation (popularly known as the Gulf stream) that keeps it running. The area is known for its temperature variations, and data available from the 1950s show that some decades are warmer, other cooler. 2005–2015 has been a cool period, but since 2016 and onwards, scientists now can see the first signs of a new warming period. The results are presented in a new article published in Communications Earth & Environment.

The researchers have used data from satellite and measurements in the ocean, modelling and a machine learning technique to document and explain for the first time the most-recent and ongoing cooling-to-warming transition of the Subpolar North Atlantic.

“In this study, we have established that these waters that are causing the current warming period originated from the Gulf Stream outside the US east coast. This means that less cold waters have made it to the eastern Subpolar North Atlantic since 2016” says co-author Léon Chafik at the Department of Meteorology and Bolin Centre for Climate Research, Stockholm University.

How can this change of temperature in the Subpolar North Atlantic be explained? By using satellite data measuring ocean sea level and currents (known as satellite altimetry) and combining it with data from ARGO floats (ocean robots), the researchers were able to track the origin of these warm waters

What consequences does this warming have? “The water in the Subpolar North Atlantic continues to the Arctic region following ocean currents. This means that any temperature change in the Subpolar region has major consequences for the polar region and the sea ice. It is very likely that this warming will accelerate the loss of sea-ice once it reaches the Arctic Ocean. This may amplify the global consequences of a reduced Arctic sea ice” says Léon Chafik

Read the article by Damien Desbruyères, Léon Chafik, and Guillaume Maze on Communications Earth & Environment, https://www.nature.com/articles/s43247-021-00120-y

Last updated: October 7, 2022

Source: Bolin Centre for Climate Research