New research on prehistoric natural disaster wins prestigious prize

The Archaeological Research Laboratory, Stockholm University, is involved in a study on how hunter-gatherer groups coped with the effects of one of the largest volcanic eruptions in prehistoric times, a study published in 2023 and now awarded the Ben Cullen Antiquity Prize 2024 for “outstanding work in the field of archaeology.”

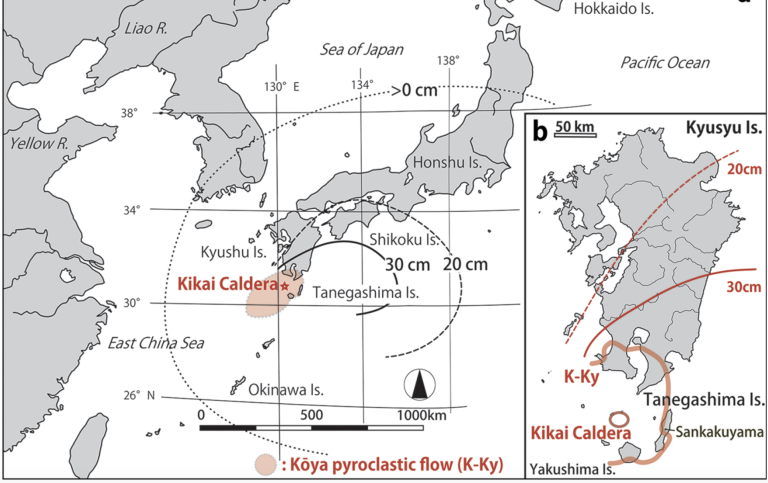

The study examines the effects of a huge volcanic eruption on groups of the prehistoric Jōmon people, a volcanic eruption that took place c. 7,300 years ago in the sea off Kyushu in southern Japan. The eruption wiped out the local population on a nearby island and devastated the island's ecosystem. Centuries later, the island was gradually repopulated, requiring adaptation to a very different environment from the one that had existed there before. The results of the study show how early human communities responded to the natural disaster by changing their subsistence and cultural practices to create new ways of living in damaged ecosystems. The study challenges previous ways of thinking about the effects of natural disasters on prehistoric cultures in archaeology.

The study is the first from the Nordic-Japanese research network CALDERA that aims to investigate the long-term cultural responses of hunter-gatherer societies to major natural disasters. The goals are to understand processes of survival, adaptation and recovery, and the ways in which long-term human-animal-environment interactions have influenced the emergence of new cultural lifestyle choices. The members of the programme are based at Stockholm and Lund Universities in Sweden and at Kanazawa and Kyushu Universities in Japan.

Professor Sven Isaksson of the Archaeological Research Laboratory was the senior author of the study:

“We are of course deeply honoured to have been awarded this prestigious international prize for our initial work on ancient disasters; it certainly encourages further research on this fascinating topic - and we already have several new papers in the pipeline.”

Professor Peter Jordan of Lund University was corresponding author of the paper:

“This first paper was very much a team effort bringing together researchers from across Japan and Sweden; it was also an opening pilot study of a much larger programme that we have launched in the last three years. We are slowly building up the research team, adding new methods and additional case-studies to get a much better and more holistic understanding of both immediate impacts, survival processes and deeper social and ecological transformations across different disaster impact zones”

“We know there was massive loss of life all across Japan, because evidence of human settlement drops away alarmingly and many large sites are abandoned under the ash,” states co-author Professor Mitsuhiro Kuwahata of Kyushu University. “At the same time, some people did survive as we see direct continuity in some of their most iconic cultural traditions, but only in a few isolated pockets, some of which are located quite close to the explosive epicentre”.

Professor Junzo Uchiyama, first author of the paper, adds:

“We wanted to get away from the assumption that this massive prehistoric catastrophe had extinguished all life; we suspected that things were more complicated, with small pockets of survival, and perhaps some ecosystems more resilient and able to bounce back faster than others – this is very much the picture we are seeing now”.

Professor Sven Isaksson, who is also a qualified survival instructor, reflects:

“In the first days and weeks after the disaster, the most important thing for survivors was to find clean water and shelter. Eventually, finding food also became important. What really interests me is what the survivors ate in the months and years after this apocalyptic event had destroyed the landscape they were used to living off, and what choices this involved; I see them gathering around hearths, cooking and sharing what they had managed to gather in the devastated landscape. From this, over time, new routines emerge, and through a combination of adaptability and tradition, the decimated communities were able to survive and rebuild in a variety of ways: this will be very interesting to investigate further.”

Read more about Antiquity prize:

Antiquity - A Review of World Archaeology

Last updated: June 12, 2024

Source: Department of Archaeology and Classical Studies