Turkey’s 2023 Elections: Successful Autocracy or Failure of Conventional Parties?

SUITS Policy Brief No. 3, October 2023

Professor of Political Science & International Relations, Özyeğin University

Summary

Democratic erosion—the incremental erosion of democracy under elected governments—is a major threat to democracy in the world. It presents a new form of authoritarianism with a new face, language, and toolkit. Turkey has experienced this erosion for two decades under governments of the Justice and Development Party (AKP) and its leader, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, making it one of the longest and most transformative examples, alongside countries like Hungary, India, and Venezuela. Before the May 2023 elections, many indicators suggested that Turkey’s vibrant and united opposition could show the world how this kind of authoritarianism can be overcome democratically. Yet Erdoğan and his People’s Alliance won the elections decisively, raising the question of whether Turkish voters had chosen autocracy. In fact, the results demonstrate that full-fledged democratic erosion may be hard to overcome with the recipes and political tools we know—in particular, by conventional political party organizations. Turkey’s pro-democracy actors may be able to prevent the consolidation of a fully autocratic regime only through a substantive makeover of the opposition parties.

The Issue

Turkey’s democracy was deficient and familiar with authoritarianism even before the AKP came to power in 2002. Turkish democracy was an illiberal one suffering from ethnic, regional, and religious inequalities, as well as the stranglehold that military-bureaucratic state actors had on civilian politics and freedoms. Underneath this deficient political system lay certain “formative rifts” unresolved since the founding of the state. At the same time, Turkey presented a pivotal democratic experience in a post-imperial, Muslim, and developing world setting. Certain elements of multiparty democracy such as popular sovereignty, peaceful rotation of civilian governments through free and fair elections, and a vibrant media able to criticize governments (but not necessarily the taboos of the state) were well-established and not challenged even by military governments.

Authoritarianism under AKP governments has been different and more complicated than past authoritarianisms. It fits with patterns of democratic erosion elsewhere in the world. It occurred under elected-civilian rather than military governments. It happened incrementally. Unlike military governments, the AKP never openly suspended democracy at any point in time. Instead, it weaponized majoritarian notions of democracy to gradually erode the previous accomplishments of democracy. The AKP did not abolish political opposition but disadvantaged and vilified it using populist-authoritarian policies and post-truth discourse. Unlike past authoritarianisms, democratic erosion proceeded under favorable conditions that should normally strengthen democracy, such as stable governments, a growing economy and middle class, and EU accession.

Such authoritarianism is hard to overcome anywhere. But before the May elections, the AKP seemed to run out of luck. A devastating earthquake and an economic crisis were expected to weaken the popularity of the incumbent. There were splits from the governing party including a former prime minister and economy minister. Most importantly, the opposition parties heeded, on the surface at least, a major recommendation of scholarship on overcoming electoral-authoritarian regimes: they united in two major pro-democracy coalitions and fielded joint candidates.

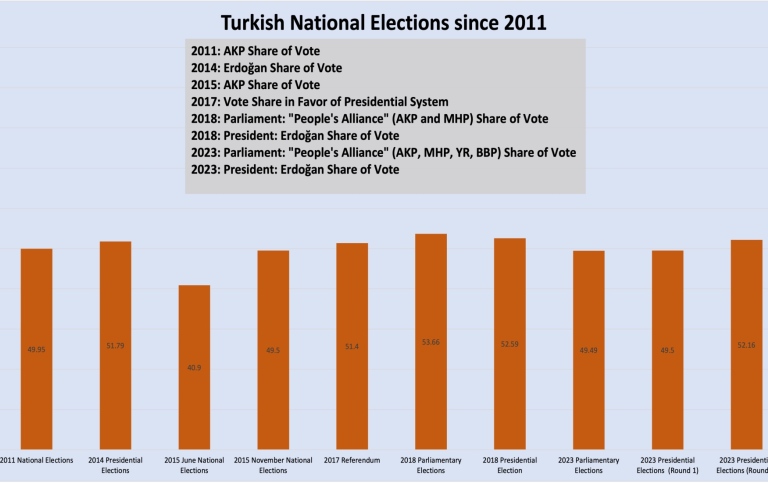

But Erdogan’s People’s Alliance, dominated by his own AKP and the far-right MHP, won about half of the Turkish votes for parliament (49.49%), gaining a comfortable majority of the seats. Erdoğan also won a constitutionally controversial third term in a runoff election against Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu, the joint candidate of the opposition, with 52.16% of the votes.

Does this mean that Turkish people have voted for autocracy? That the elections were a mere façade and unwinnable by the opposition under any circumstance?

The Analysis

What happens in Turkey cannot be appreciated without taking into account the role of polarizing politics, which divide Turkish voters into two blocs that deeply disagree over how successful and democratic the AKP and Erdoğan are. Since the crucial 2010 referendum on controversial judicial reforms that cracked the door open for molding a partisan judiciary and with the partial exceptions of the 2015 national and 2019 local elections, slightly more than half of the electorate has consistently voted for the AKP and its allies. The other half has been highly mobilized—and polarized—against it, but also internally divided.

The problem is that voter differences are not only about policy and ideology. They are about the very identities of the AKP, Erdoğan, and the country itself, and whether the country is autocratizing or democratizing.

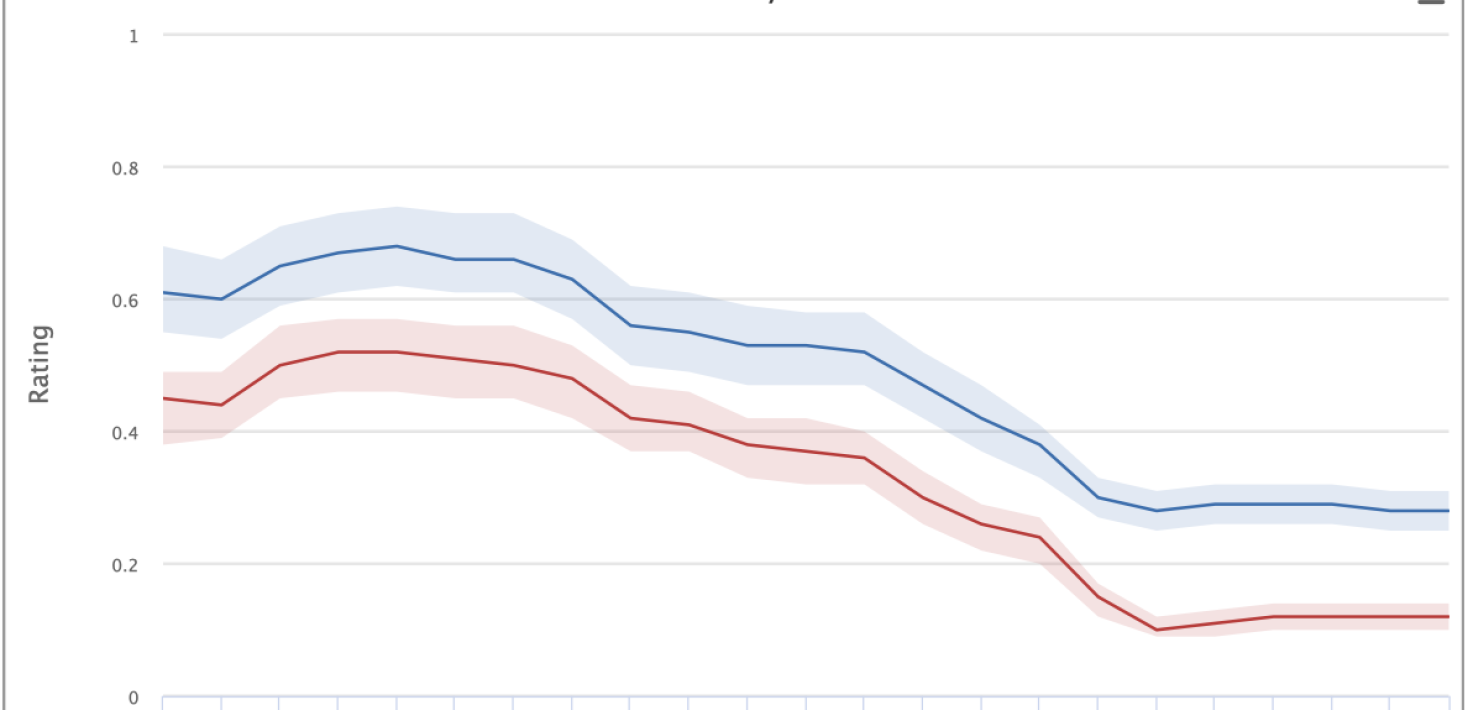

AKP supporters, of course, are entitled to have their subjective evaluation of Turkish democracy. But are they also entitled to hold views that contradict patently true, material facts? Democracy becomes deeply troubled when major portions of the citizenry hold on to post-truth beliefs, as is the case, for example, in the United States, where many Trump supporters believe that the 2020 US elections were rigged when they evidently were not. Similarly, no matter what Erdoğan supporters believe, all “objective” measurements agree—albeit to different degrees—that Turkey has been gradually, decisively, and increasingly autocratizing since the early periods of the AKP era, as Figure 2 shows.

Against this background, how can we interpret the May 2023 election results?

- The majority of Turks may not prefer democracy as we know it.

- People supporting democracy in theory can still prioritize material interests and security fears over democracy.

- Elites’ and “experts’” understanding of democracy may be defective and ignoring what people value in democracy.

- Contemporary, democracy-eroding autocrats may be more powerful than we think. They may have tools to spin truth and disinform public in ways that conventional political actors such as political parties cannot overcome unless they fundamentally reorganize to overcome their informational and other new authoritarian disadvantages.

The fourth interpretation presents the most important take-away from the May elections. (Though the second and third also carry some truth, and, paralleling global trends, popular support for a “strong executive and leadership” has grown, whether people realize potential conflicts with democracy or not).

The opposition’s real weaknesses lie in organization and program. Kılıçdaroğlu’s messages did not reach large numbers of citizens because the opposition lacks strong party organizations in touch with voters on the ground on a daily basis. They also lack innovative methods and young and entrepreneurial members to overcome technology-empowered post-truth politics. Helpless, they were ineffectual against the conspiracy theories the incumbent told the electorate with the help of “deep fake” videos, which “showed” the opposition allying with terrorist organizations and conspiring to limit religious liberties.

Opposition parties offered meaningful, educated, and orthodox policy proposals to overcome economic crisis, poverty, and authoritarianism. But they lacked path-breaking and emotionally comforting ideas and solutions to Turkey’s long-standing “formative rifts” or the “big global questions” of our era. These include the uncertainties of the international security system(s) and the immigration and climate crises. By contrast, Erdoğan’s alternative was easy to comprehend, if also twisted: “You need a strong leader and state to sail through a storm.”

Implications

Like a snowball rolling downhill, democratic erosion combined with polarizing politics can gain an unstoppable momentum. At its early stages, it is easier to stop and avoid democratic erosion through conventional and known means, such as civil and parliamentary resistance and judiciary decisions. As time passes, however, it becomes increasingly difficult to do so with conventional party politics and opposition strategies.

International and supranational democratic actors also need better tools. During the whole period of its democratic erosion, Turkey has officially remained part of its western alliances and, formally speaking, in accession to EU membership. In the new era, it may make sense to invest more in public diplomacy and subnational cooperation at party and civil society levels. To regain the Turkish public’s trust and regain the EU’s status as a democracy anchor, EU leaders should have the courage to unequivocally state that the union is fully open to a Turkey if and when she meets the membership criteria and then take steps in areas such as visa liberalization and customs union.

Given the rise of far-right populist parties and democratic erosion (and pro-democratic counter-mobilization) in countries from Slovakia to Greece, Spain, Hungary and Poland, the autocracy-democracy axis cross-cuts national and Turkey-EU borders. Therefore, better cooperation, resource pooling, and exchange of experiences between Turkish and European political parties and CSOs is more important than ever.

Takeaways

The following are important for understanding and supporting the democratic capabilities of the Turkish opposition as well as oppositions elsewhere in an increasingly autocratic environment:

- Long-term variables may better explain the opposition’s multiple failures to defeat the AKP and Erdoğan at the polls during the last two decades than short-term improvements (like party coordination) or mistakes (like nominating a sub-optimal candidate).

- It is crucial to improve opposition parties’ ability to present real solutions to long-standing problems in society and politics, and to address socioeconomic problems and deficits of the political systems that bring autocrats to power in the first place.

- Opposition parties must adjust to changing times, innovate to compete on an unlevel playing field, develop abilities to overcome polarizing and post-truth politics, and reform themselves ideationally and organizationally in such areas as membership and recruitment, communication and technology, deliberation, decision-making and finance.

- In contexts of incremental democratic erosion, democratic global actors need to better pool their resources and experiences, build international and transnational alliances, and develop novel approaches to democracy-promotion and democratic solidarity.

Further Readings

Paul Friesen, Jennifer McCoy, Rachel Beatty Riedl, Kenneth Roberts, and Murat Somer. DRG Center Learning Agenda Opening Up Democratic Spaces Original Research: Summary Report. USAID: July 2023.

Murat Somer and Jennifer McCoy, 7 Lessons from Turkey’s Effort to Beat a Populist Autocrat (Online Exclusive Research Note), Journal of Democracy, May 2023

Murat Somer, Return to Point Zero: The Turkish-Kurdish Question and How Politics and Ideas (Re)Make Empires, Nations and States (Albany: State University of New York Press, 2022)

About the Author

Murat Somer is a Professor of Political Science and International Relations at Özyeğin University, Istanbul, and a scholar of comparative polarization and depolarization, democratic erosion, democratization, and opposition strategies, religious and secular politics, ethnic conflicts and the Kurdish Question. Among many visiting positions he held, he was a Democracy and Development Fellow at Princeton University and Senior Visiting Scholar at Stockholm University Institute for Turkish Studies. A research affiliate of the Democracy Institute at Central European University, and a member of the Democratic Erosion Consortium at Brown University, he has been an active volunteer, participant and advisor for civil society and political parties and a frequent contributor to domestic and international media.

SUITS Statement

The views and opinions expressed in this policy brief are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the positions of SUITS.

SUITS is an independent research institute at Stockholm University inaugurated in 2013. It aims to contribute to a broad and well informed understanding of Turkey and Turkish affairs.

Last updated: November 1, 2023

Source: SUITS