FORCE investigates how sticklebacks affect coasts and climate

Large predatory fish have become harder to find in the coastal bays of the Baltic Sea, which are now dominated by sticklebacks. Many of these bays have also become more turbid and show signs of severe eutrophication. Scientists have seen this shift spread from the open sea to coastal environments and are now looking for explanations as to why this has happened and whether it could contribute to unforeseen climate impacts.

In one of the largest field sampling programmes of the year, the FORCE project map changes and how best to restore coastal predatory fish stocks and biodiversity. From Västervik to Östhammar, the composition of fish species, plants and algae living in 32 different bays will be analysed. In addition, samples of nutrient levels and plankton will reveal the water quality in these areas.

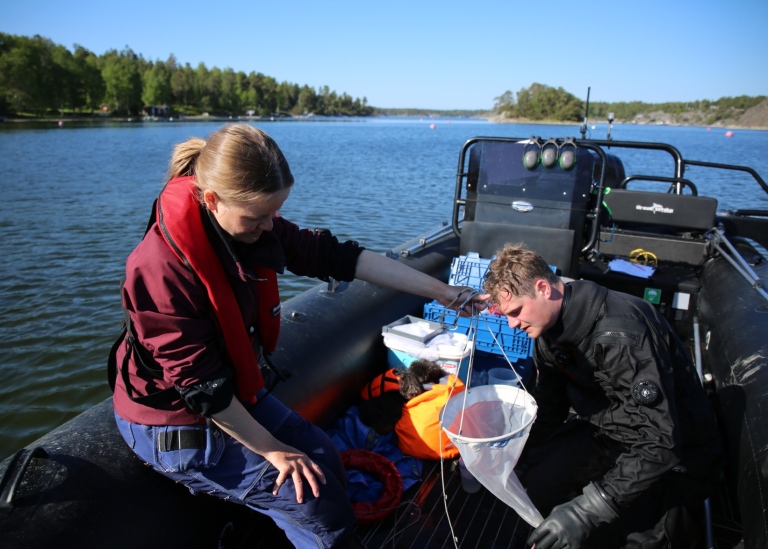

The sampling station at Krysshamnsviken in the Stockholm archipelago is a hive of activity, with several fishing nets being thoroughly sorted and rinsed on the adjacent boat jetty and beach, while samples are collected by divers and assistants in a rib boat out in the bay.

Krysshamnsviken is one of 32 sites that FORCE researchers surveyed in 2014 to investigate the relationship between fish species, vegetation and water quality. Now, 10 years later, they are back to see how these have developed.

" These bays are very different. They have different amounts of predatory fish and sticklebacks, as well as different levels of protection from fishing. The number of seals and cormorants in these areas also vary. In total, this gives us a better picture of the causes and possible measures, such as fishing closures, to improve the environmental status," says Johan Eklöf, Professor in Marine Ecology at the Department of Ecology, Environment and Plant Sciences at Stockholm University and project leader for FORCE.

Link between sticklebacks and climate change

The decline in predatory fish such as pike and perch and the increase in sticklebacks is affecting many natural values. The situation has contributed to turbid bays with more filamentous algae and severe symptoms of eutrophication. More predatory fish help to keep water areas clean and clear, and could counteract these symptoms. The researchers are now trying to find out whether stronger populations also could be linked to climate effects.

" We will investigate whether areas with a lot of predatory fish are better at storing carbon than areas dominated by sticklebacks, where carbon turnover is higher," says Johan Eklöf.

PhD student Sara Westerström is one of the members who will be looking closely at the links between biodiversity and carbon turnover in coastal environments.

" I will try to locate the carbon in the food web and see what factors that determines if the bays are carbon sources or sinks. I will mainly be looking at fish, but also at the role of vegetation and sediment," she says.

The new results will be combined with analyses of 40 years of data on how climate change and local stresses have contributed to the regime shift in the Baltic coast.

Reviewing the legislation

To determine what measures, such as protection or restoration, are most likely to strengthen predatory fish stocks and restore good environmental status, a group of researchers will look at the barriers and opportunities presented by the current regulatory framework for fisheries and other areas.

" We are looking at issues concerning fisheries management. There are many different measures that can be taken that affect fish and fisheries. Our main focus is on fisheries issues at different administrative levels, such as municipalities or county administrative boards," says Örjan Bodin, Professor in Environmental Science at the Stockholm Resilience Centre.

In order to successfully implement different adaptations and measures to protect a specific area, it is often necessary to involve several different actors. Therefore, the researchers also want to get a picture of which measures managers themselves find easier or more difficult to implement.

" Actions come at a cost, and someone may lose money on certain measures. We are trying to map the financial conflicts that exist in management," says Örjan Bodin.

The researchers are also interested in how different management rules and policies interact with each other at national level and within the EU as a whole.

" The institutional landscape is complex and we are trying to understand how the different actors interact with each other in order to achieve more effective, holistic policies," says Örjan Bodin.

The overall goal of the FORCE project is to find effective ways to improve the coastal environment of the Baltic Sea in a changing climate. In particular, the researchers stress the importance of trying to reverse the trend of stickleback dominance in many Baltic Sea bays.

" There may be an opportunity to achieve two good effects at the same time, improving water quality in the Baltic Sea and counteracting climate change at the same time," concludes Sara Westerström.

Text: Isabell Stenson

Last updated: July 3, 2024

Source: Baltic Sea Centre