Include nutrient load from horse farms in eutrophication work

Horse farms can cause significant leaching of nitrogen and phosphorus and thus contribute to eutrophication. The nutrient load from equine activities should be better taken into account in national calculations and work on eutrophication, so that measures can be taken to reduce it.

RECOMMENDATIONS

- Develop data and calculation models to include equine activities in national eutrophication calculations.

- Develop systems to facilitate the circular management of horse manure, so that more manure is used in agriculture.

- Provide advisory programmes also for smaller horse farms.

- Provide incentives, such as advice, regulations and/or support, for horse and stable owners to:

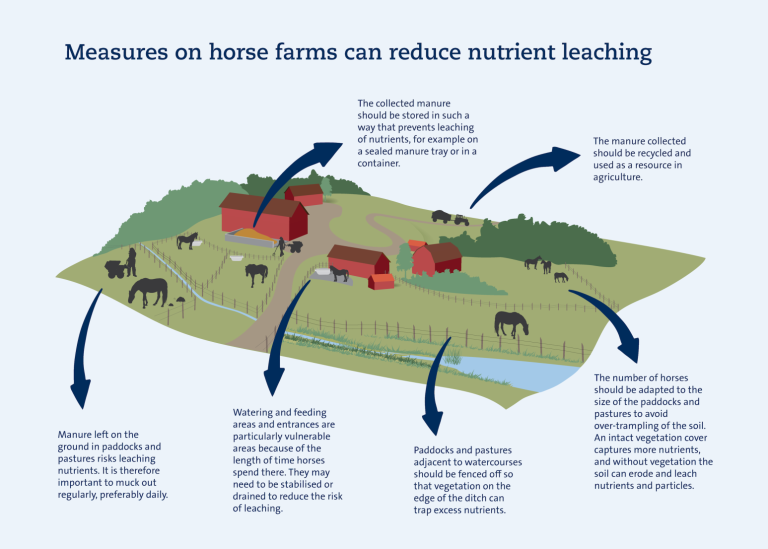

- Muck out their paddocks and pastures daily, especially when it rains,

- Handle and store manure in a way that prevents nutrient leaching,

- Fence off paddocks and pastures from watercourses,

- Adapt the number of horses to the area so that the paddocks and pastures are not over-trampled,

- Stabilise and/or drain particularly vulnerable areas of the paddocks and pastures , such as entrances and watering and feeding areas.

Sweden is a country with a large number of horses, and the sector is growing. Riding is the second most popular leisure activity after football and the role of the horse industry in tourism and recreation is growing. Horse husbandry can also increase the biodiversity of an area, as the horses help to keep the land open.

However, equine activities can also have a negative impact on the environment, and need to be more clearly included in efforts to achieve environmental objectives, particularly with regard to eutrophication.

Currently, there are about 350 000 horses in Sweden, which in comparison is more than the number of dairy cows. The size of the horse farms and the activities carried out vary greatly, but the majority of horse owners are private individuals living in urban areas and owning a few horses.

On average, an adult horse excretes as much nitrogen and phosphorus as it consumes through its feed. Since the feed is often supplied to the horse farm from outside, this means that nutrients are transported to and accumulated in areas with a high density of horses. In total, Swedish horses produce about 2.9 million tonnes of manure (urine and faeces) annually, which corresponds to 2 900 tonnes of phosphorus and 15 000 tonnes of nitrogen. Most of the phosphorus in horse manure is in the faeces, while the nitrogen is mainly in the urine.

Properly handled, horse manure is an agricultural resource, but if it is not managed properly, there is a high risk that some of the nutrients will instead leach into nearby watercourses, lakes and seas contributing to eutrophication. This risk is particularly high where horse farms are located close to water and the nutrients cannot be absorbed by vegetation or soil.

Elevated nutrient levels measured

Studies measuring the extent of nutrient leaching from horse farms have been lacking in the past. However, research has now shown that there is a link between the presence of horse farms and elevated levels of nitrogen and phosphorus in ditch water.

A recent research study showed that in areas with extensive horse activity, horse farms contribute about 30-40 per cent of the total phosphorus load and 20-35 per cent of the total nitrogen load to nearby water bodies. Levels of phosphate, the most biologically active form of phosphorus, also increased in areas with many horses. More mobile phosphorus was found in the soil of the horse paddocks than in arable land. Overall, the study showed that horse keeping can have a clear local environmental impact, contributing to the eutrophication of, for example, a lake or bay, and probably also to the eutrophication of the Baltic Sea.

When pastures are trampled, less nutrients are captured by vegetation, increasing the risk of nutrient leaching. When it rains, there is also a high risk of erosion and surface run-off, which can contribute to further nutrient leaching. Photo: Linda Kumblad

Total nutrient load unknown

Eutrophication has long been one of the major environmental problems in the Baltic Sea. Sweden is still far from achieving its national environmental objective ’no eutrophication’ – and also from achieving the objectives of the EU Water Framework Directive and the HELCOM Baltic Sea Action Plan, especially for

the central Baltic Sea.

However, it is still not known how much horse farming contributes to the total nutrient load to the Baltic Sea or to individual lakes or coastal areas. At present, only the horse manure collected and treated in agriculture is included in the national calculations of nitrogen and phosphorus sources to lakes, rivers and seas made by the Swedish Environmental Emission Data (SMED) consortium, which is the basis for the water management work on eutrophication in Sweden and for international reporting.

The lack of knowledge on how uncollected manure and other activities on horse farms contribute to nutrient leaching means that the total impact of horse farms is often not included in eutrophication calculations. It is therefore important that data is produced and calculation models are developed so that equine activities can be fully included in these calculations. This can form the basis for developing tools and encouraging actions on horse farms in the country where nutrient leaching needs to be reduced.

Character of paddocks and pastures is important

The nutrient load from a horse farm is determined by the soil conditions at the site, the number of horses kept in relation to the size of the paddocks and pastures and how the manure is handled.

Current regulations require Swedish horses to be outdoors every day throughout the year, and many horses spend most of their days outdoors. This is positive from a welfare point of view, but at the same time it is in the paddocks and pastures that nutrient leaching is most likely to occur, especially during the winter

months and when it rains.

If there is a cover of vegetation on the ground where the horses are kept, nutrients added through urine and faeces can be bound fairly effectively. Therefore, summer pastures for grazing are often not a problem. However, in the absence of vegetation, the nutrient retention capacity of both plants and soil is reduced by trampling and erosion from surface run-off. There is therefore a high risk of nutrient leaching if paddocks are over-trampled, especially if many horses are kept in a small area, for example in small winter paddocks. Allowing the soil to rest from time to time helps to maintain plant cover and increases the soil’s ability to absorb nutrients. Another way to reduce pastures stress is to reduce the density of horses.

The majority of horses (around 75 per cent) are kept in peri-urban areas, which often means that space is limited and the risk of negative environmental impacts increases. Watering and feeding areas and entrances to paddocks and pastures are particularly susceptible to trampling, as horses are kept there for a long periods of time.

SWEDISH HORSES IN FIGURES

- There are about 350 000 horses in Sweden, more than the number of dairy cows.

- The majority of horse farms have five horses or less, and three quarters of the horses are kept in urban areas.

- Sweden’s horses produce a total of about 2.9 million tonnes of manure each year, containing a total of 2 900 tonnes of phosphorus and 15 000 tonnes of nitrogen.

- Horse manure accounts for almost 20 percent of the total amount of manure from agricultural animals, but a large proportion of horse manure is produced outside agriculture.

Regular mucking out is essential

On all horse farms, but especially on small paddocks with high manure loads, it is important to muck out the paddocks regularly, preferably daily. The longer the manure remains on the ground, the greater the risk of nutrient leaching into nearby ditches and further into lakes and seas, especially when it rains and the ground becomes wet and trampled. It is particularly important to muck out entrances as well as watering and feeding areas.

The collected manure should be stored in a way that prevents nutrients from leaching into the environment, for example on a sealed manure tray or in a container. From there, it should be returned to crop production. Regular mucking out and safe storage of the manure reduces the risk of nutrients leaching into the environment.

In the past, horse keeping was more closely linked to agriculture. Horse farms also grew feed for the horses and could spread horse manure on their fields. Today’s urban horse farms often lack this link. Much of the feed, especially concentrates, is purchased from elsewhere and the stable owner has to find another outlet for the manure. Developing efficient systems and networks to facilitate the onward transport and disposal of the manure would reduce the risk of nutrient leaching.

Local conditions are important

Regular mucking out and management of horse pastures to keep the vegetation cover intact are the most important factors in reducing nutrient leaching, but other measures may be needed depending on local conditions, such as drainage and soil stabilisation in paddocks and pastures. Even in larger pastures, soil stabilisation may be justified around watering and feeding areas and entrances.

If the horse farm is close to a watercourse, it is important to fence off the paddock or pasture some distance from the watercourse. Plants along ditches and watercourses can then capture the excess

nutrients that are still leaching from the paddock or pasture. There are also measures that can capture a nutrient downstream of the source, such as lime filters or wetlands, but measures taken at, or as close as possible to, the nutrient source are usually the most effective.

Regulation of the equine industry

There are currently gaps in the regulatory framework for equine holdings. Only those horse farms that are registered as agricultural businesses, which is the minority (just under a third), are covered by the Swedish Board of Agriculture’s regulations on environmental considerations in agriculture, which include rules on how manure may be stored and spread. The rules that apply depend on the number of horses kept and whether farm is located in a so-called nitrate-sensitive area. In addition, municipalities may have special rules, for example, in zoned areas.

However, the general advice from the Swedish Board of Agriculture that manure storage areas must be designed in an acceptable manner with regard to nutrient leaching and run-off, applies to all operators. All equine activities are also covered by the Animal Welfare Act and the general provisions of the Environmental

Code, which require all operators to take measures to prevent damage to human health and the environment.

Municipalities are responsible for checking that the equine industry complies with the Environmental Code, general advice and local regulations. In practice, it can be difficult to monitor horse farms because the advice and considerations of the Environmental Code are less concrete, and therefore more difficult to monitor, than more specific regulations.

Advice and support

Many of the country’s horse farms are also excluded when it comes to advice and financial support. The agricultural sustainability project ”Greppa näringen”, has an advice programme for horse owners with more than ten horses, but advice would also be needed for smaller horse farms. Advice and compensation for

measures funded by the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) are only aimed at farms, not individuals. In other words, national efforts are needed to reach these horse owners. Horse farms run by private individuals or entrepreneurs are currently not covered by the possibility to apply for support for local measures (so-called LOVA funds).

More incentives for local measures are needed

In order to reduce nutrients leaching from horse farms, it is important to stimulate action through a variety of means, including increased knowledge, regulation, monitoring, support and financial incentives.

Information campaigns and advice are effective in increasing knowledge of the environmental impact of one’s own equine business and how it can be reduced. It may also be necessary to develop specific regulations for horse keeping and manure management, as well as increased monitoring. The pace of action

can also be accelerated by introducing the possibility for private individuals and entrepreneurs to apply for support for investments that can be costly, such as replacing inadequate manure storage areas with new sealed manure trays.

The ability to sell livestock manure offers livestock owners lower costs and more economic opportunities for good manure management. The EU’s relatively new fertiliser regulation is designed to encourage the conversion of livestock manure, for example, into transportable fertilisers such as pellets. It sets rules

for nutrient levels and the presence of contaminants, which also facilitates trade. Such organic fertilisers may become increasingly attractive as the price of mineral fertilisers rises, partly due to increased market demand and a shortage of phosphorus raw materials.

All in all, it is high time that the work against eutrophication, both locally and at the regional Baltic Sea level, seriously includes the equine industry.

About this policy brief

This policy brief is based on results from the Living Coast project and two additional studies carried out by researchers at Stockholm University, the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences and Södertörn University within the project Horse husbandry effects on eutrophication.

The researchers have measured nutrient levels at many different sites around horse farms and combined this with calculations and modelling.

Read the publications:

Kumblad, L., Petersson, M., Aronsson, H. et al. Managing multi-functional peri-urban landscapes: Impacts of horse-keeping on water quality. Ambio 53, 452–469 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-023-01955-9

Aronsson, H., S. Nyström, E. Malmer, L. Kumblad, and C. Winqvist. 2022. Losses of phosphorus, potassium and nitrogen from horse manure left on the ground. Acta Agriculture Scandinavica, Section B—Soil & Plant Science 72: 893–901. https://doi.org/10.1080/09064710.2022.2121749

Kumblad, L., Rydin, E. (2018). Effektiva åtgärder mot övergödning – en berättelse om att återfå god ekologisk status i kustområden. BalticSea2020. ISBN: 978-91-693-9453-1

Levande kust - restaurering av en skärgårdsvik (6742 Kb)

Levande kust - restaurering av en skärgårdsvik (6742 Kb)

Contact

Linda Kumblad, Systems Ecologist,

Stockholm University Baltic Sea Centre,

linda.kumblad@su.se

Helena Aronsson, Soil Scientist,

Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences

helena.aronsson@slu.se

Monica Hammer, Environmental Scientist,

Södertörn University

monica.hammer@sh.se

Last updated: May 13, 2024

Source: Baltic Sea Centre