Scientists: A fishing ban would be perfectly in line with scientific advice

2017.09.11: The European Commission's proposal to ban eel fishing in the Baltic Sea next year is welcomed by fisheries experts Gustaf Almqvist and Henrik Svedäng at the Baltic Sea Centre. They just wish the proposal had been presented much earlier.

– When a commercial species is at such a critical stage, such as the eel, this is exactly how a serious fisheries management system should act. But the Commission should have come with this proposal a long time ago, says Gustaf Almqvist.

According to him, the proposal for a total eel fishing ban in the Baltic Sea is perfectly in line with the scientific advice that ICES submitted to the EU in May this year.

– ICES is very clear: one should not fish for eel, because the stock is far too small, says Gustaf Almqvist.

The unexpected proposal for a one year ban on eel fishing came when the Commission presented its proposal on catch quotas for commercial fishing in the Baltic Sea for 2018. Usually, eel is not included in the annual quota discussions. But because of "alarming scientific evidence" about the eel's situation, the Commission felt urged to take measures.

– We must act urgently for those stocks that are still in a worrying state, like the European eel, said Karmenu Vella, Commissioner for Environment, Fisheries and Maritime Affairs in a press release.

The proposal was immediately criticised by lobbyist Michael Andersen, chief scientific adviser at the Danish Fishermen’s Producer’s Organisation. He claimed that a total ban would affect some 50 companies and about 200 people in Denmark.

–They have just decided to terminate a fishery that has taken place along the coastlines of Denmark for more than 150 years. It’s goodbye to everyone. It’s absolutely unacceptable, Andersen said to Politico.

"To maintain a fishery on an endangered species is immoral"

At the same time, others argue that the real issue here is no longer primarily about economics and jobs, but about the survival of a species.

– To maintain a fishery on an endangered species is both immoral and against the goals we have agreed upon for sustainable fisheries, says Henrik Svedäng, researcher at Baltic Sea Centre.

One the most commonly used arguments against a Swedish fishing ban on eel has been that the fishing only constitutes a very small proportion of the eels lost. But Henrik Svedäng is skeptical to these calculations and conclusion, that has been carried out by some Swedish scientists.

– It seems unreasonably low that only a few percent of the eels that migrate along the Swedish east coast would be caught by Swedish fishermen, he says.

The European eel constitutes one single stock, and there are still great knowledge gaps about the life of European eel and how they reproduce. The majority of the European eel fishery takes place in Sweden, Denmark, Germany, Spain, UK and France.

The stock is at very low levels since the late 1990s and is listed on the CITES Convention II list of endangered species. The EU adopted a regulation establishing measures for the recovery of the European eel stock already in 2007.

– Swedish eel experts have for a long time been asking for a common EU position on how to manage the eel population. We’re talking about one single stock, hence we are all equally responsible for its state. Halting all eel fishing in the Baltic Sea for a year, both commercially and recreationally, is a step towards a more shared responsibility, says Gustaf Almqvist.

Next year's fishing quotas will be decided on when the EU fisheries ministers meet in October. That is also when the proposal for a ban on eel fishing will be discussed. According to Gustaf Almqvist, there is a risk that the proposal will be voted down, but he hopes the ministers will see the necessity of a ban.

– If the ban is adopted, this means that the focus can be shifted to the even bigger threats to the eel; namely inland fishing in European lakes, the glass eel fishery and the high eel mortality caused by turbines in hydropower plants, he says.

"A ban on eel fishing is a necessary first step"

According to the two Baltic Sea Centre scientists, saving the European eel requires an all-encompassing, comprehensive approach.

– But a ban on eel fishing is a necessary first step, says Gustaf Almqvist.

And the positive effects of such a first step should not be underestimated, according to Henrik Svedäng.

– The eel in the Baltic Sea may very well constitute an important part of the entire European spawning-stock biomass. Therefore, a fishery ban can make a big difference, he says.

The EU has repeatedly used the Baltic Sea as a "model region" to shape and change European fisheries policy. This may also be the case with the proposed ban on eel fishing. The European Commission’s spokesperson in fisheries-related issues, Enrico Brivio, said in an interview with Swedish radio that, in the future, eel fishing in the North Sea and the Atlantic may also be affected.

Brivio also pointed out that the EU does not have the power to decide on inland fisheries in streams and lakes, as those are governed by the Member States themselves according to the EU Eel Regulation from 2007.

– We are confident that these countries will comply with the eel regulation, he says.

Text: Henrik Hamrén

FACTS: Tons of glass eel smuggled to Asia

There is a very high demand for elvers, or glass eel, on the black markets in Europe and Asia. For example, in June this year, the European Police Office Europol arrested 48 persons who tried to smuggle a total of 4,000 kg of glass eel out of the EU, amounting to a total value of around €4 million.

According to Europol, more than 10,000 kg of glass eel have been smuggled from the EU to China in the last year, with an estimated value of €10 million. One of the companies involved is believed to have earned around 280 million euros from smuggling glass eel in the past five years.

FACTS: The long lifetime of the eel

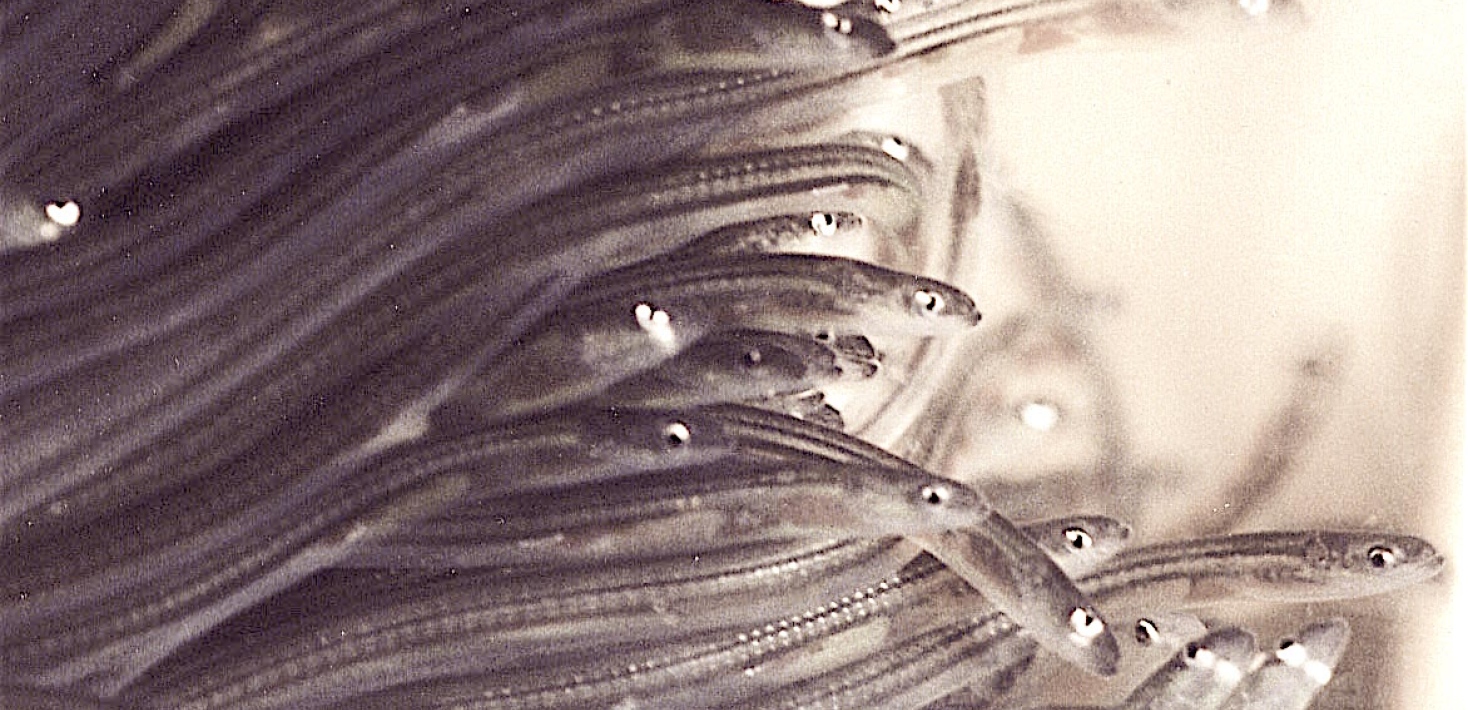

The eel is born in the Sargasso Sea in the North-West Atlantic. As elvers, or glass eel, they cross the Atlantic with the Gulf Stream and eventually end up at the European coasts. They make their way further up in streams and to lakes, where they then can live for 10-20 years before they make it back to the sea. By that time, it has turned into a fully grown (plain) eel, and (probably) begins a long journey back to the Sargasso Sea, where it plays - for the first and last time in its life - before it dies.

Last updated: May 24, 2022

Source: Östersjöcentrum