Research group Ecography Lab

The Ecography Lab at the department is engaged in an ongoing research project focusing on environmental and multispecies anthropology, with the aim of combining ecology and ethnography into one ecographic method and way on anlysis.

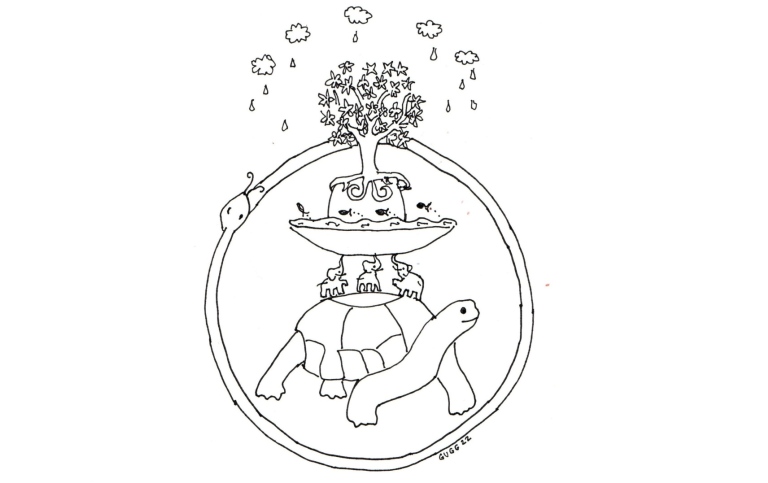

The Ecography Lab seeks to explore emerging methods that enable alternative modes of engagement with the myriad forms of life that humans share the planet with and ultimately depend on. In thinking through ‘ecography’, and in conversation with anthropology and environmental humanities more broadly, we hope 1) to break new ground by revealing new forms of connectivity, and 2) to advocate for more inclusive registers that capture already existing relations. The image above depicts The World Turtle, or Cosmic Turtle, in Hindu mythology, Chinese mythology and indigenous North American mythology. It illustrates the belief that a turtle or tortoise and other animals support the world. The image and its wider cosmology illustrate the early insights of various societies that life is always entangled and dependent on other beings, i.e. ways of knowing that we want to bring forward and explore further.

Group description

Environmental anthropology has increasingly addressed key ontological and methodological questions by incorporating several different critical approaches within the field. ‘Multispecies’ ethnography, ‘more-than-human’ and ‘other-than-human’ research focus on how to, with anthropological tools, reach across the species barrier and engage with the life and worlds of animals, plants, fungi or microbes. Anthropologists have taken ideas on the ‘species turn’ – “when species meet” (Haraway 2007) – and blended them with the classic anthropological studies of small-scale subsistence societies (cf. Boas 2016 [1888], Evans-Pritchard 1968 [1940], Rappaport 1968; MacCormack & Strathern 1980, cf. Lien & Pálsson 2021), the discipline’s focus on relations (Strathern 2020), non-Western cosmologies and ethnographic methods. Eduardo Kohn, for example, suggests that an ‘anthropology of life’ is on the horizon, taking inspiration from indigenous ontologies, asserting that all life, in essence, is composed of an ‘ecology of selves’ (Kohn 2013). In addition, Tim Ingold has long insisted, all living organisms exist in, and must be understood in, relation to the environment. Hence, to understand the making and unmaking of this world, Ingold suggests, requires an alternative mode of engagement, ‘from ontology to ontogeny. Ontology is about what it takes for a thing to exist, but ontogeny is about how it is generated, about its growth and formation’ (Ingold 2021:8).

The Ecography Lab is a space to further push these debates by discussing which methods anthropologists can use to ethnographically and relationally study more-than-human worlds. These worlds are marked by distinctive connections and disconnections (Candea et al. 2015), localisations and delocalisations, human and non-human work (Besky & Blanchette 2019), cohabitation and exploitation, alienated within the imperial debris of capitalist industrialisation in ways that enable ongoing extractivism (Stoler 2008, Tsing 2015, Tsing et al 2017). We suggest that the heuristic term ‘ecography’ can help us discuss how to methodologically enhance ethnography (to write/describe a people) with its focus on human society, to better describe the relational environmental dynamics between diverse life forms. We use ‘eco’ to refer both to ecology as ‘a system of relations’ and to its older Greek meaning oikos ‘system of the home’ including its more-than-human organisms and materials. Half a century ago, Ernst Haeckel used the term to refer to ‘the total relations of the animal both to its inorganic and to its organic environment’ or even the investigation of such totality (Haeckel cited in Stauffer 1957:141). Ecography, in that sense, gestures to the entangled webs of interconnected life co-constituting home, underlining the need to move beyond anthropocentric perspectives as life forms are dependent on each other. It also aims to consider the wider political and economic structures of industrial capitalism, the dominant human-induced driving force that is impacting planetary ecological relations and threatening long-term survival.

The Ecography Lab is a space to discuss and research how we can methodologically engage with such a relational anthropology of different life-forms, where ecography can be used to decentre the human in our methodological toolkits, moving beyond species to look at various more-than-human worlds as homes to multiple life forms. We aim to methodologically explore hierarchical systems of relations and entangled webs of exploitation and cohabitation that include humans, other organisms and inorganic materials. By considering wider relational becomings and the politics of degradation and dispossession, we hope to move beyond ‘multispecies studies’, ‘more-than-human’ and ‘other-than-human’ approaches.

Methodologies and research at the Ecography Lab also opens up for discussions about how we can incorporate methods from natural sciences, social sciences, and artistic research to develop a research methodology for categories previously seen as ‘voiceless’, such as rivers, mountains and biotopes, while critically reflecting on the implications of human representatives appointed to ‘speak on behalf’ of ‘natural’ entities. We also require new temporal tools, for not only are different life-worlds entangled, different temporalities are too (Metcalf and van Dooren 2012). We can no longer limit research to a sole subject or object; networks of relations are key (Latour 2005), and points of relationality provide points of view, directions from which one can perceive the dynamics of connections and disconnections as life unfurls together with our interlocutors. Hence, by embracing new sensory methods and theoretical tools that trace the leaking trails of ecological relations, we may be able to comprehend other ways of being and relating to the world. By critically comprehending humanity relationally, as incorporating multispecies, technologies, infrastructures, more-than-human work and different forms of governance, we may be able to reduce the negative impact some ecosystems have endured as a direct result of capitalist industrial practices that have for far too long objectified the ‘environment’.

References

Besky, S. & Blanchette, A. (eds). 2019. How nature works: Rethinking labor on a troubled planet. University of New Mexico Press.

Boas, F. 2016 [1888]. The central eskimo. Read Books Ltd.

Candea, M., Cook, J., Trundle, C. and Yarrow, T. 2015. Introduction: reconsidering detachment. In: M. Candea, J. Cook, C. Trundle and T. Yarrow (eds.) Detachment: Essays on the Limits of Relational Thinking. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Evans-Pritchard, E.E. 1968 [1940]. The Nuer: a description of the modes of livelihood and political institutions of a Nilotic people. Clarendon.

Haraway, D.J. 2007. When species meet. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Kohn, E. 2013. How Forests Think: Toward an Anthropology Beyond the Human. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press.

Ingold, T. 2021. Correspondences. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Latour, B. 2005. Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor Network Theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lien, M.E. and G. Pálsson. 2021. Ethnography beyond the human: the ‘other-than-human’ in ethnographic work. Ethnos 86(1).

MacCormack, C.P., & Strathern, M. 1980. Nature, culture, and gender. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press.

Metcalf, J. and van Dooren, T. 2012. Temporal Environments: Rethinking Time and Ecology. Special issue of Environmental Philosophy, 9 (1).

Rappaport, R.A. 1968. Pigs for the ancestors: ritual in the ecology of a New Guinea people. Yale University Press.

Stauffer, R.C. 1957. Haeckel, Darwin, and Ecology. The Quarterly Review of Biology, 32 (2).

Stoler, A.L. 2008. Imperial debris: reflections on ruins and ruination. Cultural anthropology 23(2).

Strathern, M. 2020. Relations: An Anthropological Account. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

Tsing, A.L. 2015. The mushroom at the end of the world: On the possibility of life in capitalist ruins. Princeton University Press.

Tsing, A.L., E. Gan, & N. Bubandt (eds) 2017. Arts of living on a damaged planet. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Group members

Group managers

Bengt G Karlsson

Professor

Members

Bengt G Karlsson

Professor

Ivana Macek

Associate Professor

Erica von Essen

Docent

Tomas Cole

PhD

Gudrun Dahl

Professor emerita

Annika Rabo

Professor emerita