Research project Risk management and financial networks in the textile trades in 18th century Stockholm

The project "Risk management and financial networks in the textile trades in 18th -century Stockholm. Tailors, court tailors, fashioners, dressmakers and sewers as creditors and debtors in bankruptcy files, c. 1765-1799" is led by Professor Klas Nyberg.

The project focuses on the strategies the tailoring and textile industry in Stockholm developed to deal with the difficulties that followed Stockholm's economic and demographic stagnation from the 1760s through the mid-1800s. How was the production of clothes organized and what kinds of tailors existed at the time? Were the guilds dissolved at the end of the early modern period due to collaborations with textile manufacturers and textile retailers or were larger tailors organized within the guild? During this period, tailors made uniforms and bourgeois civilian clothes as well as pure luxury clothing for the court and nobility. We know that silk waistcoats and accessories were standardized and the number of illegal seamstresses grew at this time, but it was only in 1834 that ready-to-wear actually became legal to sell. Between 1739 and 1846 the entire manufacturing system to which all textile producers, dyers and cutters, with the exception of linen weavers, belonged had a dissolving effect on the guild system.

Project description

The purpose of this survey is to use an institutional approach to examine the financial relationships of guild-affiliated tailors with each other and with other entrepreneurs in the textile industry. The study aims to show the extent to which the industry organized cross-industry alliances for managing crises in the credit networks in the aftermath of the 1763 European trade crisis.

First, the debt structure for various types of tailors in bankruptcy is examined. In part, the degree to which tailors were creditors in bankruptcies within the entire textile industry is mapped: textile manufacturers (silk, wool and linen), wholesalers who imported wool and silk, textile artisans (linen weavers, dyers and cutters) and textile retailers (silk and remainder clothing dealers, linen and scrap cloth dealer). Textile manufacturers were subject to a special court system called hallrätt from 1739 until 1846, while craftsmen belonged to the guild system according to the 1726 guild order. Wholesalers and retailers obeyed the laws of the merchant guilds.

My preliminary studies of the bankruptcy material show that three types of tailors were active in Stockholm's textile market during the period. In addition to the majority of tailor craftsmen, who were only titled as tailors, there were court tailors and ladies' tailors (“fruntimmersskräddare”). Everyone seems to have belonged to the craft guild, even though they cut and sewed various kinds of fabrics produced by the silk, wool and linen manufacturers. Manufacturing under the hallrätt system was recorded in detail in the factory statistics from 1739-1846, while the scope and turnover of the craft guild can only be estimated based on tax records.

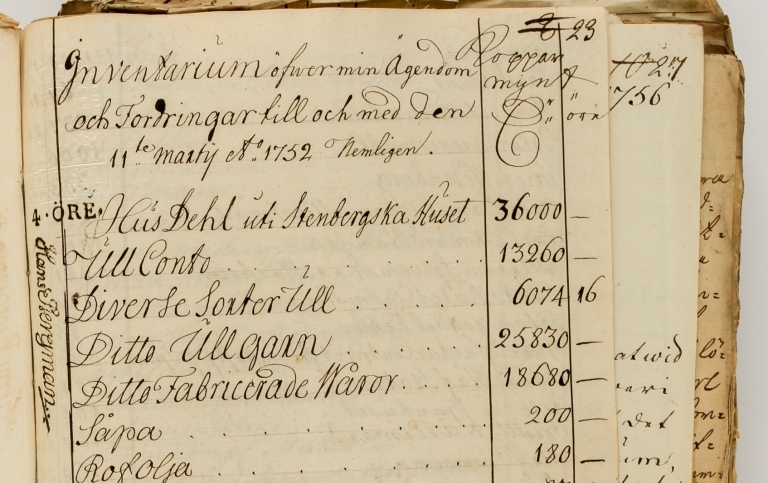

The strategies of tailors and other actors are examined through their lists of debts, lists of claims and preserved disputes in the primary material of the bankruptcy files. The notaries' ledgers show which creditors actually monitored or had their claims monitored in bankruptcy cases. Finally, bankruptcy judgments show how the City Hall court's lawyers assessed the actors' conflicting claims in the submissions in the disputes with each other. The bankruptcy diary's withdrawn bankruptcy cases show the extent to which settlements were made. Taxation ledgers make it possible to see the income levels of all types of actors.

Project members

Project managers

Klas Nyberg

Professor

Publications

Project related