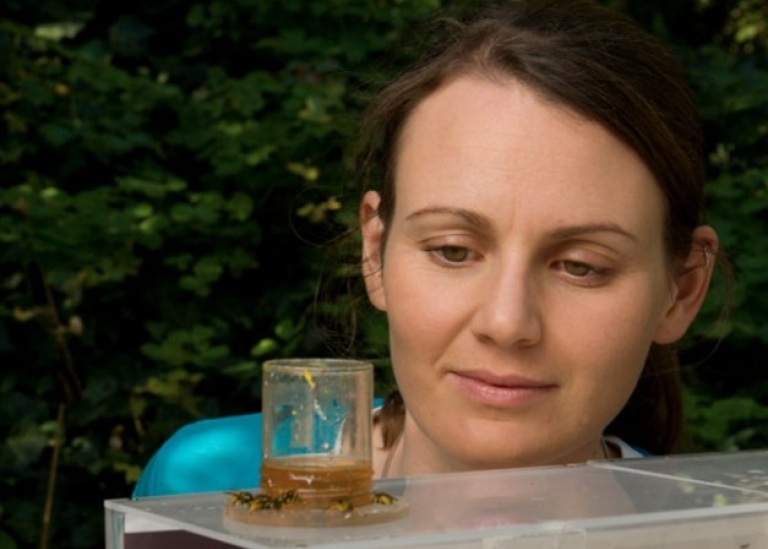

Emily Baird and the mysteries of the insect brain

Emily Baird is a Senior Lecturer in the Department of Zoology. The following interview with Emily was conducted in September 2018 and updated in January 2024.

What does a bumblebee see?

What does the world of a bumblebee actually look like? That's a simple way to describe Emily Baird's research - but answering the question is not so simple. For many years, Emily has been trying to understand the importance of visual information for insects, especially bees and bumblebees.

These little buggers are amazingly adept at navigating, both to pollen- and nectar-rich plants and back home to the nest. But what do they actually see? Because insects are so small, and have such tiny brains, we actually have a chance to understand how they work through comparative studies of behavior and anatomy. We'll come back to how to do this in a moment.

From South Australia to Northern Europe

Unlike the bumblebees, Emily herself hasn't been very good at navigating home, quite the opposite - she now lives as far away from the original nest as you can imagine. She grew up on a farm in Australia, surrounded by horses and cows, chickens and dogs and cats. No wonder she became interested in animals!

But her interest in psychology and neuroscience was just as strong, so when she started university in Canberra, it was impossible to choose; she got a double bachelor's degree after studying biology, philosophy, anthropology and more. What interested Emily most was how the brain works, from every conceivable aspect.

Luckily, she got involved in what she calls "the optimal project": training tambin in different visual environments. The work eventually led to a PhD on vision-guided flight control in bees. The project also had a technical aspect, something that still interests Emily. If we can understand how insects navigate, perhaps we can also improve the navigation of flying robots?

After a short stay in Bielefeld, Germany, Emily was offered a postdoc in Lund. Lund has long had a vibrant research program in sensory biology with an emphasis on comparative vision research, so it was the best possible research environment for Emily.

Advanced imaging technology

o map the anatomical structures of the insect brain, Emily and her team used a technique called micro-CT. CT stands for computed tomography. The technique involves obtaining a large number of X-ray images, taken from different angles. These can then be used to reconstruct the three-dimensional structure of an organ, for example, and the method is now common in medical diagnostics.

Micro-CT works in the same way but produces images with much higher resolution, making it possible to image an insect's eye at the micrometer level. The main model organism in Emily's research so far has been the dark earth bumblebee (Bombus terrestris), a species that is readily available because it is commercially exploited as a pollinator in greenhouse tomato crops. But Emily also looks north and wonders if the special bumblebee species of the mountains see the world differently, living in an environment bathed in light all summer. In addition to bumblebees, Emily has also used dung beetles and flat horned mosquitoes as experimental organisms.

To Zootis in Stockholm

After ten years in Lund, Emily came to Stockholm University in 2018 and set up her own lab at Zootis with micro-CT and other equipment. She says she was impressed by the faculty's resources in areas such as microscopy, and she enthusiastically speaks of a "vibrant international community" with great opportunities for fruitful collaborations.

How do students learn best?

During her years in Lund, there was a lot of teaching for Emily. There were beginner courses and master's level courses and everything in between. She often had to read up on areas she wasn't particularly familiar with, which was of course a challenge. But she says it gave her a better understanding of how students experience their studies and the difficulties they may face.

Learning and behavior is something that interests Emily a lot, not only in insects but also in students - it is again a question of how the brain works. Emily does not believe that traditional lectures are the optimal way to utilize teachers. That's why she's tempted to try a method called 'flipped classroom', where students first watch recorded lectures and then discuss and process the material with the teachers. There are already some fantastic lectures online!

In her spare time

In her spare time, Emily prefers to be outdoors, unless she is traveling. She grew up with a love of horses but stopped riding when she left Australia. So now, whenever she explores her hometown or the outdoors, it's the Apostle horses that come to mind.

Last updated: July 10, 2024

Source: Department of Biology Education